FOREWORD

The author, Gerd Michael Müller, born in Zürich in 1962, traveled as a photo-journalist to more than 50 nations and lived in seven countries, including in the underground in South Africa during apartheid. In the 80 years he was a political activist at the youth riots in Zürich. Then he was involved in pioneering Wildlife & eco projects in Southern Africa and humanitarian projects elsewhere in the world. As early as 1993, Müller reported on the global climate change and in 1999 he founded the «Tourism & Environment Forum Switzerland». Through his humanitarian missions he got to know Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama and other figures of light. His book is an exciting mixture of political thriller, crazy social stories and travel reports – the highlights of his adventurous, wild nomadic life for reportage photography .

(please note that translation corrections are still in progress and images will follow soon)

In 1996 I made a trip to Malaysia to celebrate 50 years of independence from the British crown and after the state celebration with all Asian heads of state, I first traveled around Malaysia by car for ten days and visited Taman Negara National Park in the rainforest. The country’s fascinating charms range from dreamlike beaches on the islands of Lankawi and Tioman in the north on the Thai border, to cultural strongholds such as Penang or daring climbing tours on Mount Kinabalu, or even the wildlife paradises in the two national parks of Niah and Gunung-Mulu. After the round trip through Malaysia and the side trip to Langkawi I flew to Borneo and landed in Sarawak with the aim to explore the situation of forest clearing for palm oil production, the thereby threatening situation of the head hunters and the destroyed habitat of the Orang Utan.

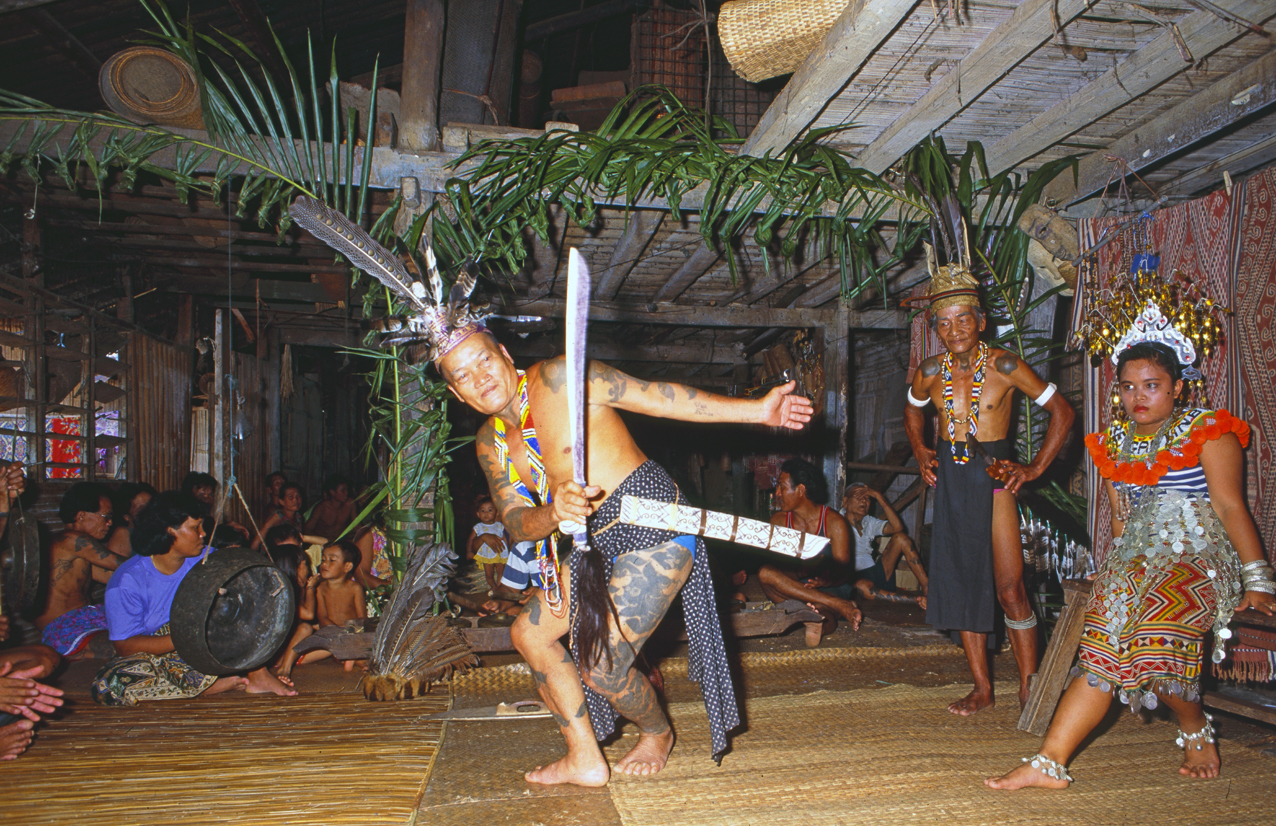

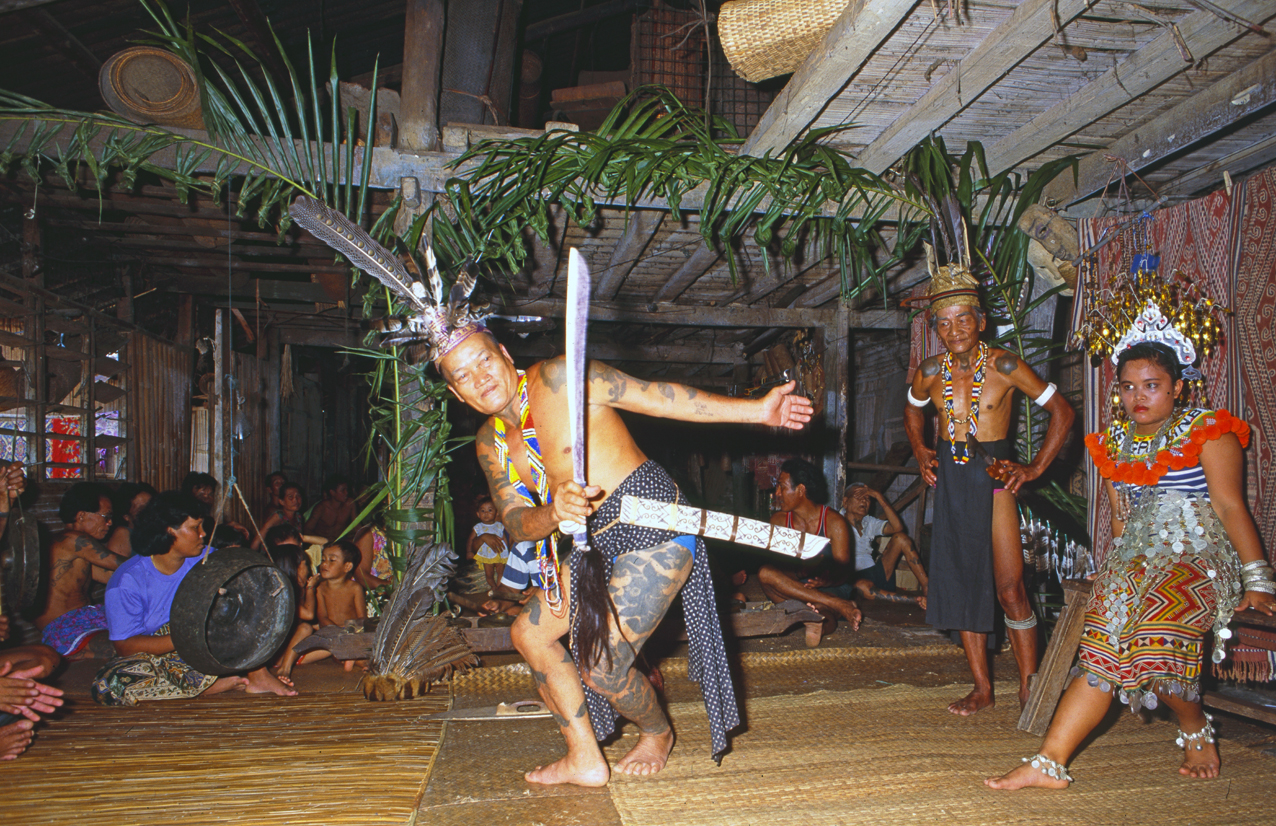

At Lake Batang Ai in Sarawak on Borneo I started the expedition into the rainforest and hired a guide with a dugout canoe to lead me to the Iban Headhunters living here. After two days‘ travel from Lake Batang Ai, paddling a canoe upstream through a sea of deforested tropical tribes flowing downstream, I ended up in one of these remote longhouse villages. The days of decapitating intruders with the parang, the dreaded long knife, and hanging the grisly trophies in the form of shrunken mini-skulls from the beams of the longhouses are thankfully over. But I have yet to see such shrunken skulls, and I don’t want to end up that way.

The longhouses of the head hunters are built on stilts, up to 100 meters long and have a continuous wide corridor leading to a longitudinal veranda. In the longhouse, one dwelling is then lined up next to the other. So that everyone knows what the other of the clan is doing. Unfortunately, due to my lack of language skills, it was very awkward to have conversations with the headhunters about their traditions and way of life, since no one understood English. Communication was only through sign language, observation and a „low-level“ communication. In the hallway, which is a good five meters wide, talented Iban women sit and weave elaborate bast mats, shape vessels out of clay, or sit at a loom while older men and women supervise the children. In the evenings, the younger men join them, drink their tuak (palm wine) and tell stories about hunting, field work or their work on the plantations.

Unfortunately, after a short time I came down with malaria, which laid me completely flat. Although I had swallowed some „Lariam“ tablets, I still felt very bad. Shaken by fever cramps and checkmate, I lay around for three days like a dead fly in the „longhouse“ of the headhunters, before I could go back by dugout canoe to a jungle camp that had a radio station. There I tried with Switzerland over the radio connection and the telephone handset held elsewhere to the radio, to take up contact with my family. When then at home in Switzerland the tape recorder instead of a connection came, because it was there in the middle of the night, I said only briefly that I wanted to say goodbye, because I would probably not survive the night. After that, I lay down outside under the starry night sky, shaken by more bouts of fever. I wanted to die at least in the open air and not in the tiny, stuffy wooden hut in which I had been quartered.

What happened now was unique and should shake my distinctive sense of reality fundamentally. Whether it was only halucinations or whether I was actually brought back from the ascension, is not clear to me until today. In any case my astral body took off and then I saw purely optically already the stars with comet-like rapid speed coming towards me and felt pulled weightlessly up into the orbit and glided so to speak like the spaceship „Enterprise“ which jetted with light speed through the orbit towards the starry sky. But since the stars cannot come toward me, I realized that I probably took off like an angel and now raced toward the sparkling firmament, unless my fevered brain was doing its antics and hallunzigone vision with me. Either way the journey to the stars was as exciting as it was enlightening. Shortly thereafter, a scream and screech rang in my ears and I heard my daughter and her mother howling in horrified tones, but not understanding any of their words. „What the hell are they doing up here,“ I thought for a moment, and then my little daughter’s voice occupied my mind so much that my light-speed flight to the stars abruptly lost momentum and I completed a loop back to Earth, telling myself that the time to depart had not yet come, since there were two people who needed me. So I swallowed three more „Lariam“ tablets and had now reached the dose for an elephant, as a tropical doctor told me a few days later. But after that it slowly went uphill again.

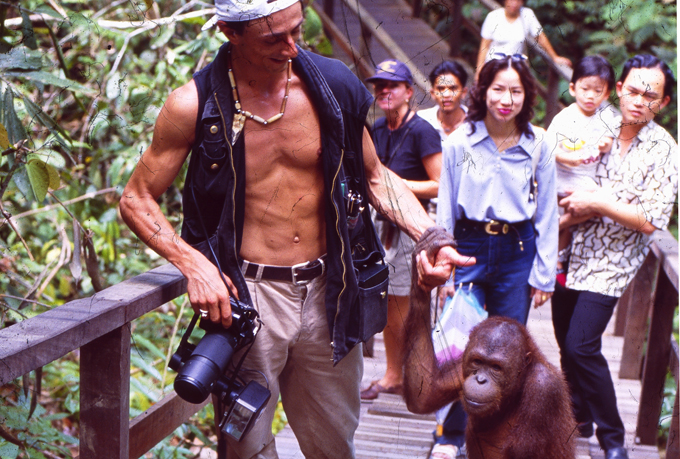

With the help of the jungle camp residents I got back on my feet after two days, traveled on to Kota Kinabalu to the Orang Utan Rehabilitation Station in Sepilok and arrived just at the right time, because at 11:00 a.m. the feeding of the Orang Utan was taking place from a platform about two kilometers further in the forest interior. Two groups of tourists had already started walking before me on the wooden walkway that leads a good two meters above ground into the rainforest to the large visitor platform and the two feeding places in the trees behind it. As I slowly approach the scene with my telephoto lens and recognize the young orangutans on the feeding areas, as well as the adult orangutan hanging from the wire rope that was stretched between the two feeding areas, I also heard the shouts of individual visitors who wanted to persuade the large orangutan to turn around, as he cheekily stuck his butt out at all of us. The isolated calls bounced off his butt. As a photographer, I was also interested in the fat guy showing us his face. So I emitted a few loud grunts, as I had heard them before, and apparently hit the right note. And lo and behold, in no time the orangutan turned around, showed his smacking face and looked curiously over at us. Perfect: „Ready for the photo shoot?“ Click, click, click.

After that, I watched as the babies got their food and gobbled it down, then abruptly disappeared back into the trees. But I wanted to get back to the rehab station before the others after the feeding, so I made my way back down the dock before the others. As I tried to sneak past a young handicapped orangutan, with a chopped off but already healed arm, lying backwards on the walkway and thus blocking the passage, he grabbed me by the lower leg. What was I supposed to do? When I wanted to gently release his hand that was clutching my leg, he simply grabbed me by the wrist, whereupon we both, the young orangutan and the still feverish and sweaty photographer ran hand in hand through the jungle to the station. That was a wonderful feeling. The orangutan could have taken me right up into the treetops with his buddies. That didn’t work, but I made a damn good appearance in the rehabilitation ward when we arrived there, still hand in hand, like good old friends, to talk to the ward manager.

My report about the „endangered“ apes was well received in the Swiss media and besides seven daily newspapers that printed the report, also the „Brückenbauer“ with a circulation of millions published the story with an appeal for donations, whereupon several tens of thousands of Swiss Francs were donated and benefited the Orang Utan Rehab Station in Sepilok. The apes became known through the Swiss environmental and human rights activist Bruno Manser, who vehemently campaigned for the indigenous people of the rainforest, the former head hunters, and then disappeared without a trace and was possibly murdered by the „timber mafia“, to whom he was a thorn in the flesh.

Bruno Manser from Appenzell lived in Borneo from 1984 to 1990, making records of the fauna and flora of the tropical rainforest and learning the language and culture of the Penan, a nomadic people group on Borneo, and living with them. In 1990 he had to flee to Switzerland after he was expelled by the Malaysian government and declared an „undesirable person“. A bounty of 50000 dollars was also placed on his head. In 1993, Manser participated in a fasting action and. a hunger strike in front of the Federal Parliament in Bern to protest against the import of tropical timber. In 2000, despite an entry ban and a bounty on his head, he traveled from the Indonesian part of Borneo (Kalimantan) across the green border into the Malaysian Sarawak to the Penan and was never seen again. Since then, Bruno Manser has been considered missing and was officially declared dead in 2005.

The orang utan, the „forest man“ in Malay, has been threatened with extinction since the mid-1960s. Despite international species protection agreements, at that time still extremely restrictive trade agreements and the two capture and rehabilitation stations on Semengho in Sarawak and Sepilok in Sabah on the Malaysian island of Borneo, the close relatives of Homo Sapiens are more acutely endangered than ever. Greed for tropical timber and palm oil is destroying their habitat, the primary forest. The destruction of their refuges has left them isolated in small groups. The clear-cutting of the rainforest destroys not only the material but also the spiritual basis of existence of many primitive peoples, because the imagination of the Orang Ulu, Melanau, Kenzah and Kajan tribes assumes that their ancestors live on as birds, insects or animals in their native environment. Thus, with each tree cutting, the cultural heritage is desecrated and mercilessly destroyed. And by far the largest segment of the population in Sarawak, the Bidayuh rice farmers believe in the symbiosis of the human and plant life cycle and believe that after their death, people return to earth as drops of water that fertilize the soil and give life.