FOREWORD

The author, Gerd Michael Müller, born in Zürich in 1962, traveled as a photo-journalist to more than 50 nations and lived in seven countries, including in the underground in South Africa during apartheid. In the 80 years he was a political activist at the youth riots in Zürich. Then he was involved in pioneering Wildlife & eco projects in Southern Africa and humanitarian projects elsewhere in the world. As early as 1993, Müller reported on the global climate change and in 1999 he founded the «Tourism & Environment Forum Switzerland». Through his humanitarian missions he got to know Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama and other figures of light. His book is an exciting mixture of political thriller, crazy social stories and travel reports – the highlights of his adventurous, wild nomadic life for reportage photography .

It was once again an old „airline connection“ that brought me to Lebanon, because I always wanted to go there. In my youth Lebanon was the „Switzerland of the Middle East“, a cultural stronghold in the Orient, a melting pot of jet set, dropouts and creative music freaks. Moreover, from the Beeka Plain came, in my eyes, the world’s best shit, that is, hashish made from hand-harvested hemp flowers, of the finest taste and feel, and provided with particularly intense and fragrant flavors. Tempi passati, when I finally arrived in Lebanon.

By then the country was already scarred by war with Israel and economically devastated, as well as socially deeply divided between ethnic groups such as the Shiites, Sunites, Druze and Maronites, as well as other ethnic groups. Beirut was a hot ground and a tricky mission, even for a crisis-tested reporter. The biggest problem was that I didn’t speak or understand a word of Arabic. I have visited many conflict regions and experienced the critical hot phases myself, but I did not dare to venture into the Hezbollah quarters without appropriate contacts and connections or a locally familiar person in the background. But in order to establish contacts, the time until my departure within a few days was too short.

In addition, one of the most important protective factors in my work is not only to speak the language of the population, but if possible not to be recognized as a foreigner or stranger at all. I could not use these aces here. During my short stay I was stopped and briefly interrogated by the Lebanese army three times in one day alone and in the Hezbollah quarters it became even more uncomfortable. Almost on every third corner you were stopped as a foreigner and asked who you were and what you wanted here. Hezbollah is Iran’s most important ally in Lebanon, not only from a military but also from a political point of view, because Hezbollah, together with its allies, is the most important political force in the imploded country on the Levant. But Lebanon serves Iran as a military front against Israel and that outside its own territory. Therefore, the Assad regime in Syria is also an ally and Iran’s only strategic partner.

Due to the precarious security situation and without local contacts or adequate protection, I withdrew from this neighborhood and arrived instead at the Palestinian refugee camp of Shatila. There, a Palestinian refugee showed me the three massacre sites. The Sabra and Shatila massacre is the name given to a cleansing action by Phalangist militias, i.e. Christian Maroni soldiers, directed against Palestinian refugees living in the south of Beirut. In September 1982 – in the middle of the Lebanese civil war – the two mentioned refugee camps, which were surrounded by Israeli soldiers at that time, were stormed and hundreds of civilians were massacred by the Christian, i.e. Phalangist militias.

Since the fighting was a conflict between Christian militias and Palestinian fighters, the international outrage was ignited by Israeli co-responsibility. This is because after the Israeli military withdrew to a security zone off the Israeli border, Syria took military control of the area around the refugee camp. And they allowed hundreds of Palestinians to be massacred. Since Syria was also interested in weakening the „PLO“ fighters and Palestinian nationalists who remained in Lebanon, the situation of the people in the refugee camp became even worse. In the course of the camp wars, the Shiite Amal militia perpetrated a massacre of civilians in the same Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in May 1985, which was condoned by Lebanese and Syrian army units. The Lebanese civil war continued until 1990, and the massacre was subsequently deemed a genocide by the United Nations General Assembly on December 16, 1982. So much for this tragic story of the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

After exploring Beirut a bit, I made a side trip to Byblos, which is one of the oldest cities in the world and has been inhabited for over 7000 years. The port has been used since the Stone Age. The town was also made famous by the legend of Adonis, who died a day’s journey away at the source of the Adonis River. The rise of Byblos came with the need of the Egyptian Pharaohs for Lebanese cedar wood for their ships. Then came the Greeks, who gave the place its present name, when papyrus played the greatest role in the rise of the Phoenicians, because it was here that the first alphabet was created, and Byblos therefore became the birthplace of writing and the Bible. After the Asyrians and Babylonians, the Persians conquered the area until Alexander the Great imposed the Greek influence. Finally, the Romans also arrived in Byblos. A city that historically has always played a great role and has experienced different influences and currents.

Considering that in the 1970s and early 1980s Lebanon was a very liberal country with a pronounced French savoir vivre, and Beirut, as well as Tehran in Iran and Kabul in Afghanistan, were strongholds of pleasure and attracted the international jet set as well as dropouts on their way to India, Beirut now only radiated a pathetically run-down „disaster chick“. The traces of wars and bombings are unmistakable and very depressing. When, in 2020, the entire port blew up and pulverized the surrounding neighborhood, the state, which had been bled dry by a number of clans, had reached the end of its rope. In addition, Lebanon is also carrying another burden, that of the more than one and a half million Syrian refugees.

A hopeless situation for the cedar country. With the rented car I drove from the temple ruins of the Unesco World Heritage Byblyos to Tripoli and then up into the high mountains to Bsharreh to the Maronite rock monasteries. Unfortunately, there was not enough time for the Bekka plain. Today Lebanon is an imploded, highly corrupt, stale state and the religious groups are more divided than ever. But let us remember that Europe was also shaken by religious conflicts for over 150 years until a secular society emerged.

The Gebran Museum near Bscharreh in the lebanese Mountains near the Cadisha Valley and Cedar forest

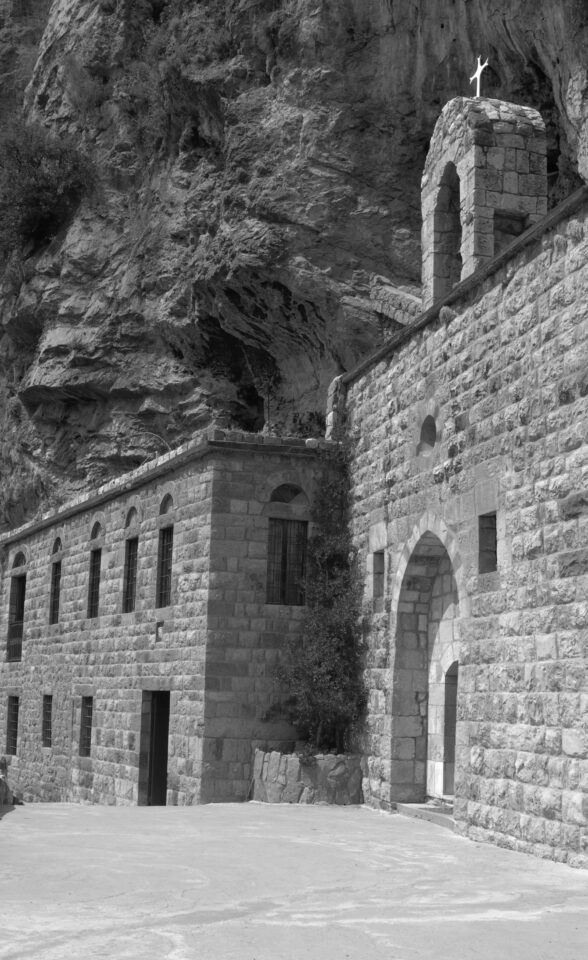

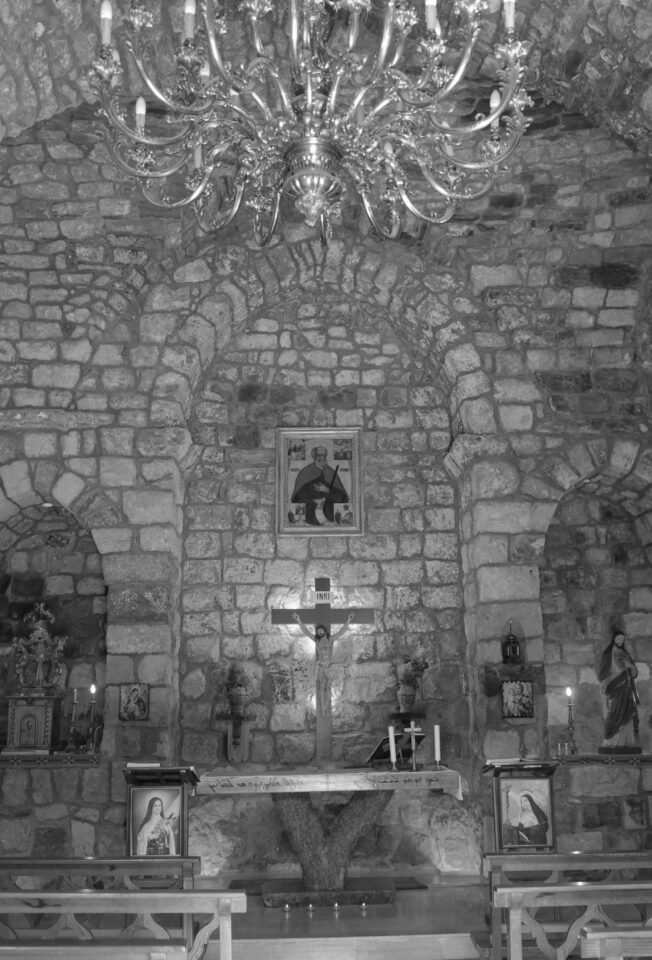

Antonios Tarabay Al Tannoury Kloster im Qadisha-Tal. Monastry in the Qadisha-valley. Shallita and Assia are the names of two famous hermits who lived and died here during the 17th-18th centuries. The Lebanese Maronite Order was founded at this monastery in 1696. When the Order was divided between the Lebanese and the Aleppine monks in 1770, the Monastery of Mar Elisha was granted to the Aleppines (who became known as the Maronite Mariamite Order in 1969). Except for some small sections, most parts of the monastery building date from the 20th century.

The Cross Path on the old road of Saint Elishaa Hermitage. Becharry Top of the Valley of the Saints

Lebanon: The historic village Byblos with the castle and the Amphitheater has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

Lebanon: The illuminated Mohammad al Amin Mosque of Beirut at night.

Lebanon: Beach area of the luxury Mövenpick Hotel in Beirut-City

Lebanon: side street near Beirut harbour

The historic village Byblos with the castle has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

Lebanon: The historic village Byblos with the castle has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

Civil war building ruins at the Elias Sarkis Boulevard, the green line during the war.

The bar on top of the luxury Mövenpick Hotel in Beirut at night is a hote spot for wealthy lebanese people.

Lebanon: The historic village Byblos with the castle has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

The Cross Path on the old road of Saint Elishaa Hermitage. Becharry Top of the Valley of the Saints

Lebanon: The historic village Byblos with the castle and the Amphitheater has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

Lebanon: The historic village Byblos with the castle and the Amphitheater has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

Antonios Tarabay Al Tannoury Kloster im Qadisha-Tal. Monastry in the Qadisha-valley. Shallita and Assia are the names of two famous hermits who lived and died here during the 17th-18th centuries. The Lebanese Maronite Order was founded at this monastery in 1696. When the Order was divided between the Lebanese and the Aleppine monks in 1770, the Monastery of Mar Elisha was granted to the Aleppines (who became known as the Maronite Mariamite Order in 1969). Except for some small sections, most parts of the monastery building date from the 20th century.

Byblos historic castle. Die historische Ritterburg in Byblos

Lebanon: The historic village Byblos with the castle and the Amphitheater has an old history that goes back to five thousen years b.c.

The Gebran Museum near Bscharreh in the lebanese Mountains near the Cadisha Valley and Cedar forest

Lebanon: The marina of the luxury Mövenpick Hotel in Beirut-City

Lebanon: The Mohammad al Amin Mosque in Beirut-City