FOREWORD

The author, Gerd Michael Müller, born in Zürich in 1962, traveled as a photo-journalist to more than 50 nations and lived in seven countries, including in the underground in South Africa during apartheid. In the 80 years he was a political activist at the youth riots in Zürich. Then he was involved in pioneering Wildlife & eco projects in Southern Africa and humanitarian projects elsewhere in the world. As early as 1993, Müller reported on the global climate change and in 1999 he founded the «Tourism & Environment Forum Switzerland». Through his humanitarian missions he got to know Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama and other figures of light. His book is an exciting mixture of political thriller, crazy social stories and travel reports – the highlights of his adventurous, wild nomadic life for reportage photography .

(please note that translation corrections are still in progress and images will follow soon)

Politically sensitized by the youth unrest of the early 1980s, as an opponent of nuclear power plants, a pacifist, and a conscientious objector on the political left, as well as focused on South Africa from a humanitarian point of view through my professional activities during my apprenticeship at the „Oerlikon Bührle“ Waffenschmiede, I decided to fly to Johannesburg at the end of 1986 with the aim of getting to know the tense situation and the inhumane conditions on the spot. I had made contacts with ANC exiles in London and had also made contacts with the „Anti Apartheid Movement“ (AAB) in Switzerland. And since one of the tour guide colleagues in London had a brother living in South Africa and we were planning an expedition to the Okavango Delta in neighboring Botswana in 1987, I had an ambitious and adventurous program ahead of me.

First, my former supervisor in London and I lived for a few weeks in the posh white man’s quarters in Hillbrow. The first thing to get used to was the black housekeeper who was included in the rent! Then, of course, there were the restrictions on the black population in all areas of public life, that inhuman racial segregation and discrimination, with the corresponding pass laws for the respective ethnicities. There was also an Indian community in Durban and the Malay mixed race in Cape Town, which was quite complicated, especially the resettlement plans, which were also put into action. Thus, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs and the NGO „Black Sash“, over half a million black people were forcibly resettled in the homelands and dispossessed. This gave the white farmers access to their large farms in high-yield regions.

I carefully familiarized myself with the local conditions, visited the „Khotso House“ in Johannesburg where some resistance organizations like the „Black Sash“ but also the „UDF“ union had their offices. The house was spied on around the clock and often searched by the police. Many committed „ANC“ activists were arrested, tortured or imprisoned without charge. One of the most prominent victims of the apartheid regime, along with Nelson Mandela, was Stephen Biko. Biko participated in the founding of the grassroots Black Community Programs (BCP) movement in 1972, which was banned by the government. He was also involved in the establishment of the „Zimele Trust Fund,“ a fund for victims of the apartheid regime. In August 1977, he was arrested by the security police for violating conditions. They interrogated and tortured Biko and dragged him unconscious 1000 kilometers to Pretoria, where he died on September 13, 1977. Biko’s violent killing led to an international outcry. Biko became a symbol of the resistance movement against the apartheid regime.

I arrived in South Africa just at the time when the „New Nation“, one of the last liberal, critical papers of the Catholic Bishops‘ Conference under Desmond Tutu was banned and closed down and conducted a last interview with the just dismissed editor-in-chief Gabu Tugwana, which appeared at that time in the „WOZ“ (weekly newspaper) and was thus the first foreign journalist to see and photograph the decree of the hated Minister of the Interior. The apartheid regime censored or banned many newspapers until all possible critical voices were silenced. Spending on internal security, that is, on maintaining the racist apartheid system, gobbled up more than 20 percent of the gross domestic product.

Then I dared to take the suburban train from Down town Johannesburg to Soweto, that is, to the black townships, at that time an extremely dangerous thing to do. Once you arrived in Soweto, you were quite alone and conspicuous as a white person at that time. Fortunately I had long hair and looked neither like a Boer nor like an Englishman, which probably kept many from killing me in the townships. Then the curiosity rather grew in them, what I had to look for here and so I could calm them down thanks to my „ANC“ contacts made in London and Zurich, so that they trusted me and introduced me to the Town Ships.

For a few weeks I lived with a family of eight in a small wooden shack surrounded by tens of thousands of other wooden shacks without light, electricity or water. The goal was to experience the living conditions of the blacks and their everyday life within the framework of the racist laws first hand and to explore them with my own eyes. Soon it was possible for me to move freely and safely with my black friends in Soweto. And so I myself was scared as hell when I suddenly stood in front of an armored vehicle of the „SADF“ (South African Defence Force) again and firearms were pointed at me.

Mandela’s release and his visit to Switzerland

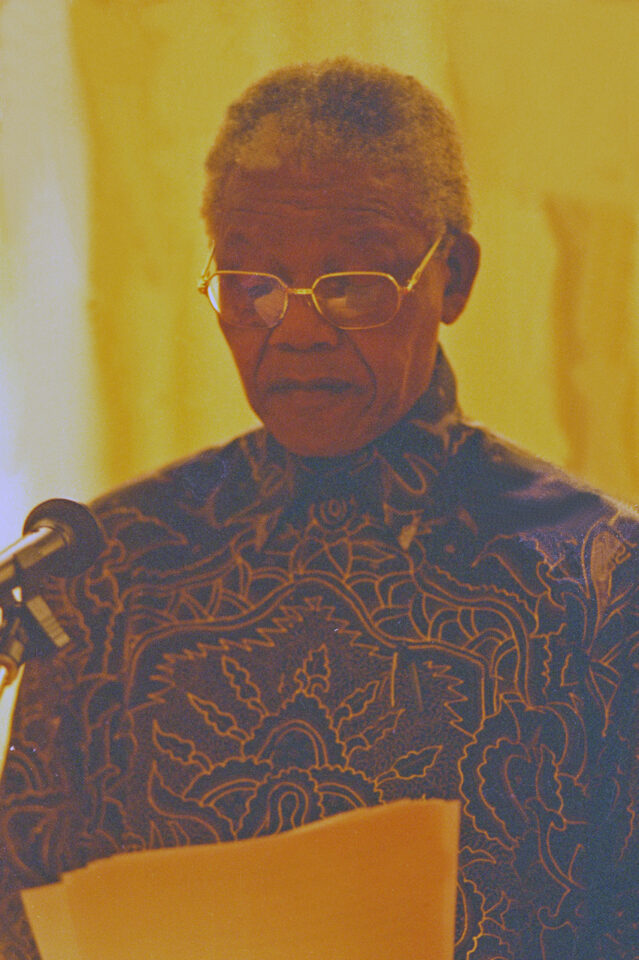

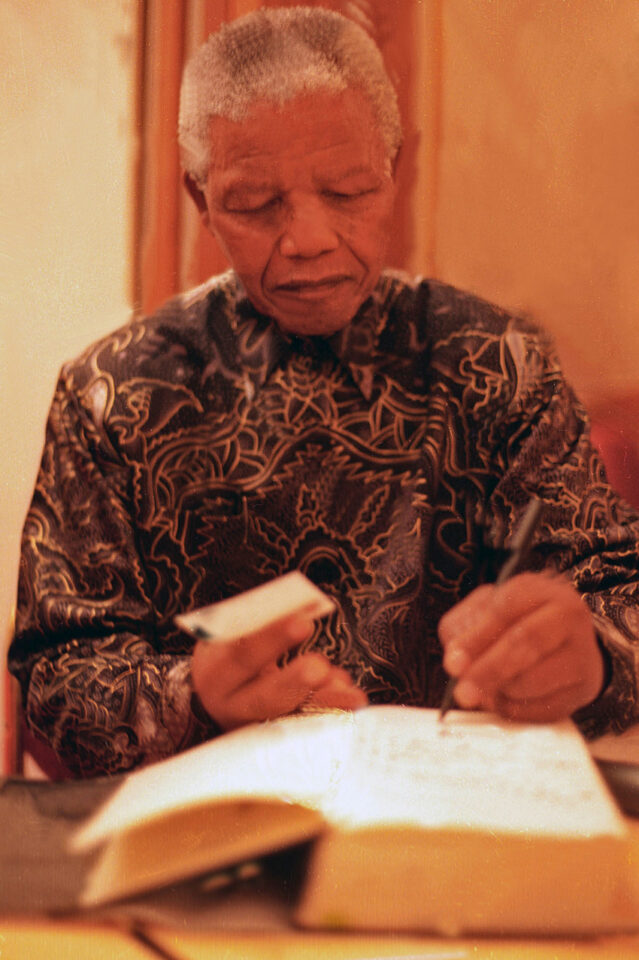

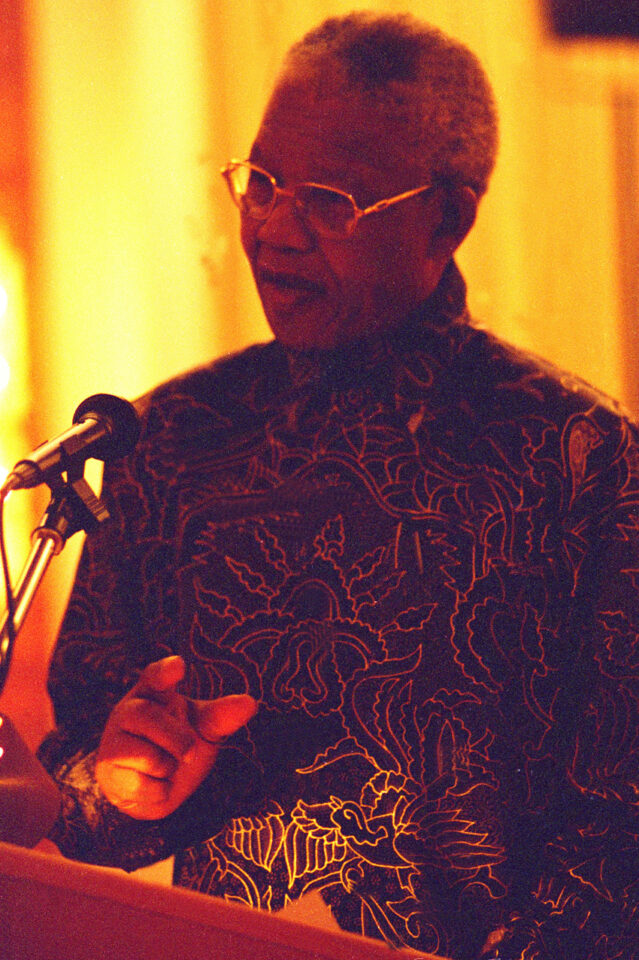

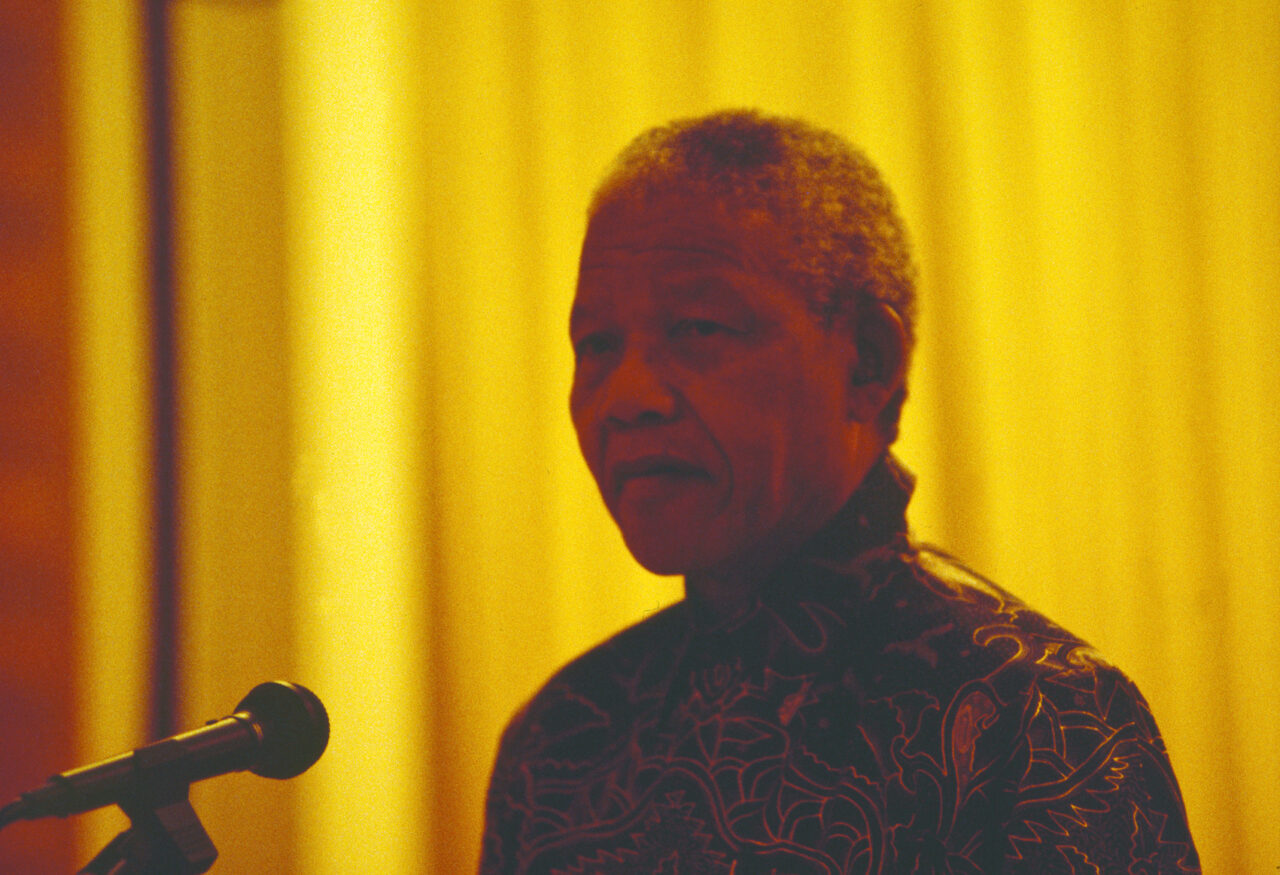

From this first trip I developed a deep connection with the country that I visited more than 20 times and met Nelson Mandela twice. The first time shortly after his release here in Soweto, the second time, as President of South Africa and newly elected Nobel laureate in Zurich’s „Dolder Hotel“ in front of the „class politique“ and economic elite (National Bank President and bank representatives), when Mandela spoke about his vision of a new South Africa as a „rainbow nation“.

I was also invited to this historic meeting and took a few pictures of Mandela. However, I was not prepared for the fact that he would be blinded by flash light as a result of his lost eyesight due to his long imprisonment, and I had the wrong film speed in the box without flash light. I could have slapped myself for not having another roll of film with me. When Mandela mingled with the crowd at the aperitif after his speech, I stayed discreetly in the background. But obviously Mandela had a good memory and very attentive eyes, maybe he even remembered where and when in Soweto I stood in the crowd of blacks as the only white person shortly after his release.

In any case, this prompted him to approach me and ask if we had ever met. I was taken aback. When I replied, „yes in Soweto,“ he amazingly extended both hands to me. That was very touching! The feeling that I had made a difference and that I had received a prominent thank you and unbelievable appreciation. Thereupon everyone in the room stared at me and wondered who the long-haired freak was here. Fortunately, this remained a secret between me, Mandela and the South African ambassador in Bern, Dr. Konji Sebati, with whom I was once a guest at the embassy in Bern for a high-ranking event.

Through this contact, I came to work as a travel journalist and PR consultant at that time, and received a PR mandate for the South African tourist office „SATOUR“. In addition, I received the PR mandate of the South African airline („SAA“) for years. I owed this to the diplomatic balancing act between the underground contacts (of which only a few knew) and the contacts to the white elite, which also took place very discreetly. And also to the sad fact that the Swiss played a central role in South Africa in the gold trade, in the „AKW’s“, in the military support of the apartheid regime with fighter jets and pilot training, and ultimately in both the debt restructuring and the transformation process, and thus also took over the gold trade. To this day, Switzerland has remained the gold trading superpower, handling nearly 80 percent of the precious metals trade.

At this point, let’s look back just under two decades, to August 5, 1962, when Mandela, together with Cecil Williams, was arrested during a car ride near Howick in Natal on the charge that he was leading the banned „ANC“ underground. The arrest came after he had spent nearly a year and a half at liberty and working in the political underground, interspersed with public appearances for the „ANC“ abroad. The start of the trial was set for October 15, 1962. As a result, Mandela was sentenced on November 7, 1962, to five years in prison for inciting public disorder (three years in prison) and traveling abroad without a passport (two years). He undertook his own defense at this trial.

After the verdict was announced, he was taken to Robben Island prison at the end of May 1963, but was soon brought back to Pretoria after the rest of the „ANC“ leadership was arrested on July 11. From October 7, 1963, Mandela stood trial in Pretoria in the „Rivonia“ trial with ten co-defendants for „sabotage and planning armed struggle.“ On April 20, 1964, the last day of the trial before the verdict was handed down, Mandela gave a detailed explanation in his four-hour prepared speech of the need for armed struggle because the government had not responded to appeals or to the nonviolent resistance of the nonwhite population in its quest for equal treatment and had instead enacted increasingly repressive laws.

On February 11, 1990, Mandela was released from prison after 26 years. President Frederik de Klerk had arranged this and days earlier had lifted the ban on the African National Congress (ANC). Mandela and de Klerk received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for their services. On the day of his release, Mandela gave a speech from the balcony of the City Hall in Cape Town, and days later he made another appeal to the 120,000 or so listeners at the soccer stadium in Johannesburg. There he presented his policy of reconciliation („Reconciliation“).

South Africa 94: ICRC interventions in the „ANC-IFP“ civil war

After the apartheid regime collapsed due to the UN boycott and South African resistance, a bitter power struggle between the „ANC“ (African National Congress) and Buthelezi`s „IFP“ (Inkhata Freedom Party) ensued. The civil war claimed X-thousand victims and turned tens of thousands into refugees. Another tragedy, because previously the white regime had forcibly relocated hundreds of thousands of black people like cattle in the course of racial segregation.

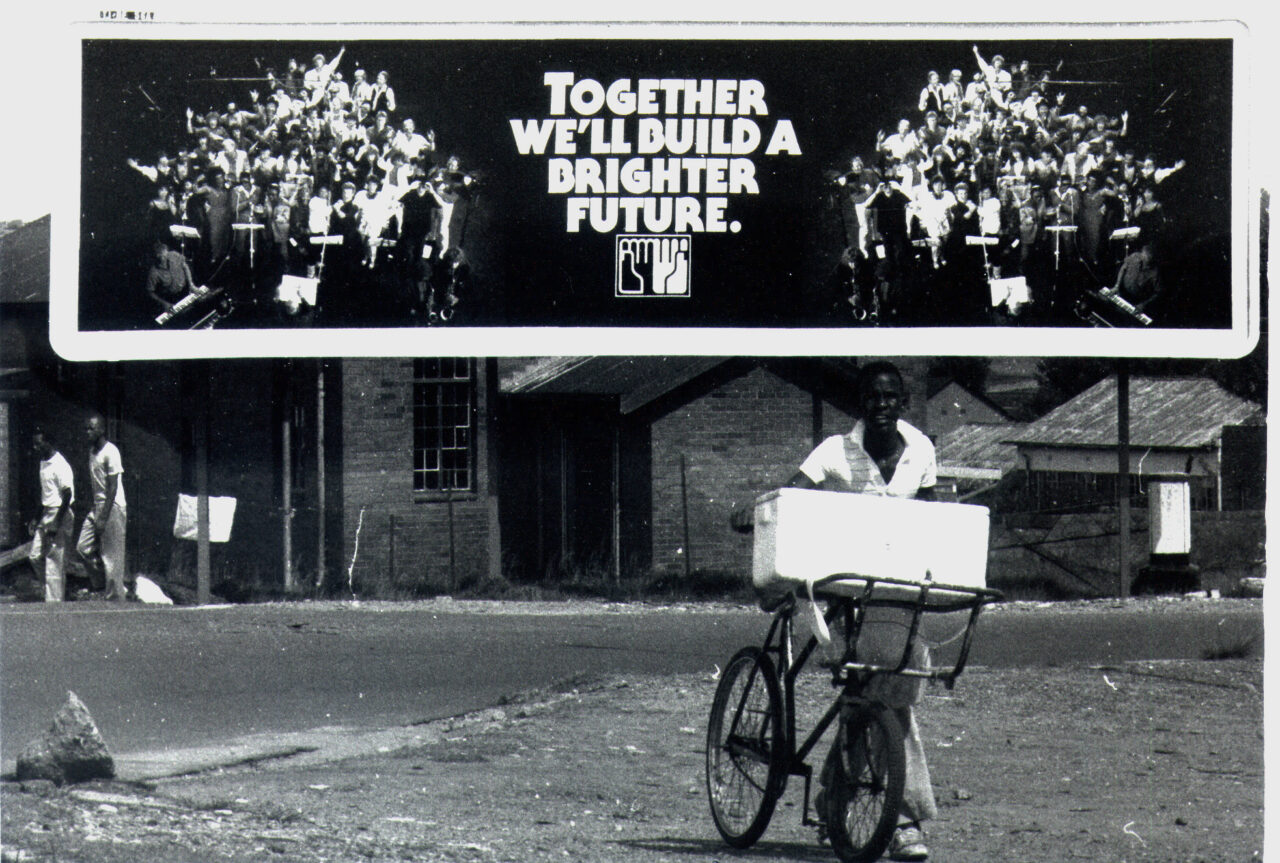

Now there was again a wave of displaced people in the country and trench warfare among blacks. It was a declared strategy of the outgoing or endangered rulers to sow discord among the blacks by all means, and so the Botha regime put up Buthelzi as a counter-candidate to Mandela. All means of destabilization were used and the seeds were sown. The civil war was terrible.

In post-apartheid South Africa, people were concerned with one thing above all: the ever-growing violent crime rate. Whereas in the past the police had primarily targeted political opponents, the security forces and politicians were now fighting an almost hopeless battle against brutality and criminality. The „taxi/minibus war“ in Durban claimed numerous innocent lives for years. In Cape Town, a gang war raged among 80,000 youths, and Johannesburg was also the scene of numerous crimes.

As a tourist or business traveler, one felt the „atmosphere of fear“ intensely. The police forces operated like paramilitary organizations and had a bad reputation in the respective cities. Unemployment was almost 40 percent, causing widespread poverty and crime to skyrocket, aided by the impotence and corruption of the self-absorbed judicial and police apparatus, which was paralyzed in the wake of radical reconstruction. More than 60 people were killed every day in South Africa, for a total of about 20,000 annually. South Africa’s prisons were bursting at the seams. Criminal investigations remained unresolved for years. Even young people under the age of 14 were often imprisoned for long periods.

At the end of 1993, I accompanied a friend of mine, Daniel S., who was stationed in Johannesburg as an ICRC/Red Cross South Africa delegate, on his trip to the refugee camps to assess the situation there, to help the victims and to support the peace efforts to stabilize the country with a view to a democratic constitution and government for the „Rainbow Nation“. We went to the then hotspots „Margate“ and „Ladysmith„, „Ezakhweni“ and „Emphangeni„, „Mfung“ and „Obizo“ as well as „Empendle“ logged the burned houses and the dead, talked to bereaved families and tried to mediate between the conflicting parties.

A difficult, if not almost hopeless task. In 1994, another interesting meeting took place, with Miss South Africa Basetsana Kumalo and at her side Kwezi Hani, the young daughter of Chris Hani, who had just been murdered. Chris Hani was Secretary General of the South African Communist Party (SACP), a senior member of the „ANC“ as well as Chief of Staff of its be-armed arm „Umkhonto we Sizwe“ (MK).

As the end of apartheid loomed in the early 1990s, he was one of the most popular leadership figures in the „ANC“ after Nelson Mandela. Hani was assassinated in April 1993 by the Polish immigrant Janusz Waluś. Behind it was a plot whose mastermind was former Member of Parliament Clive Derby-Lewis of the Konserwatiewe Party. The goal was to destroy the negotiation process that was supposed to lead to the end of apartheid. A diabolical plan that worked.

The meeting with Basetsane took place in a casino and was obviously being watched. It was, after all, a red-hot time and the spying on political actors and their families and surroundings was a well-known fact. And so I also became a target of observation. First a black man and later two white gentlemen tried to question me discreetly but emphatically. And another illustrious person tried to contact me even in Gabarone, in Botswana, and to involve me in South Africa’s internal power struggles. I rejected all overtures and thus escaped unscathed from the turmoil of the political power struggles.

In February 1996, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) set up by Mandela and headed by Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu. began to come to terms with the crimes committed during the apartheid era. This was used primarily to settle accounts with and dismantle Winnie Mandela, who had suffered much more and had to fight harder than her husband in those years after Madiba’s release. It was the ANC leadership at the time that decided Winnie had to distance herself from Nelson Mandela.

Winnie’s star was always below Nelson’s, but she was the real power woman who was Mandela’s eyes and ears during his imprisonment, and it was she who mobilized the masses. For some groups, the social improvements achieved during Mandela’s time in office, including those related to the AIDS crisis, did not go far enough. Critics also complained that the apartheid regime’s crimes were not sufficiently punished. Children under six and pregnant and nursing mothers received free health care for the first time; in 1996, health care became free for all South Africans. Steps toward land reform were taken with the Land Restitution Act (1994) and Land Reform Act 3 (1996).

During his term, numerous apartheid-era laws were revoked. The army and police were reorganized. As part of my humanitarian work in South Africa, thanks to the Zulu healer Credo Vusama Mutwa, I was also able to visit Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town (where Nelson Mandela spent the last years of his imprisonment) in 1997 with a Canadian team of UN health inspectors. The prison, designed for 3,000 inmates, held about 7,000 prisoners. Nearly 30% of the inmates were HIV-positive at the time and many prisoners were held for years without charge, quite a few died. The conditions we encountered were shocking. A spoonful of food in the prison kitchen was enough to give me staphylococci and streptococci. It was also pedagogically disconcerting that the only toy in the children’s playroom was a plastic firearm. In this way, a new generation of poverty-driven criminals is bred from childhood on.

I met the Zulu Sangoma, Bantu writer & historian Credo Vusama Mutwa in the „Shamwari Game Reserve“ together with Dr. Jan Player, the rhino rescuer and „Wilderness Leadership School“ founder. All night long this educated man told me the spiritual secrets and ethnic connections as well as cultural characteristics and peculiarities of the Bantu people from North to South Africa. He was also the first to recognize climate change and to explain to me what it means for the peoples and regions when one or another beetle, various insects, the turtles or other species of wild animals and marine mammals become extinct and this leads to droughts and plagues. In prophetic foresight, Credo recognized the conflicts that would arise from this, as well as it always comes to conflicts with dams, because that changes the livelihood of many people in several countries. He also predicted the plagues we have experienced in the last 20 years.

And that was a good 10 years before the first IPPC climate report. Only I was traveling with my daughter and her mother and had appointments and meetings regarding wildlife and eco-projects and could not stay here to help Credo with the „Kaya Lendaba“. I was torn. The Zulu healer wanted to heal the wounds of the Rainbow Nation and build a multicultural village at the Shamwari Game Reserve where all South African ethnic groups would be represented. It was to serve as a beacon for the reunification of South Africa and help end the conflicts.

I would have gladly trained to become a „sangoma,“ or healer, because Credo believed I had the qualifications and the spiritual worldview. This filled me with pride and would probably have been a groundbreaking switch in my life. For originally I wanted to work as a game ranger in one of these emerging wildlife reserves. I couldn’t imagine anything more rewarding than working as a wildlife manager in an intact environment that was protected or worth protecting. So I kept traveling to Botswana, South Africa and Namibia to fulfill a little bit of this dream and it was always a great feeling to be out in the bush and wilderness.

Now let’s move on to the current situation at the Cape of Good Hope, which has by no means become rosier. After the outrages of the apartheid regime came a new black elite, who enriched themselves just as shamelessly as their white predecessors. Two examples:

2011: Gadaffi’s billions in Zuma’s and Ramapho’s hands in hiding

Aziz Pahad was appointed by Mandela as deputy foreign minister in 1994 and worked for the government from 1999 – 2008. Before that, he collected donations for Mandela’s election campaign and also received about 15 million from Gadaffi. The Libyan dictator also supported Tabo Mbeki. But Mbeki did not want to comply with Gadaffi’s wish to become „King of Africa“ and refused to support him, which led to Gadaffi buying Jacob Zuma as his next choice and helping him to become South African president. Through the decades of relations with the „ANC“ Gadaffi planned to have in the worst case a retreat and base abroad from where he could start the counterrevolution and for this he had a part of his unimaginable fortune of about 150 billion dollars (Forbes) flown to Johannesburg on 26 December 2010.

The plane landed directly on the military base Waterkloof, which was deserted on the 2nd day of Christmas. Reportedly, there were a total of 179 such flights from Tripoli, all of which were carried out by military pilots. Flight data was also erased, after each operation. Allegedly, the value of the cargo, which was in ICRC crescent labeled containers with Libyan dialect from Syrte was about 12.5 billion. US dollars. Besides mountains of cash also tons of gold and diamonds. Serbian George Darmanovitch, a Secret Service agent known as Zuma’s henchman, photographed the shipment upon arrival in Johannesburg and confirmed to investigators that the money was picked up by trucks from the „ANC.“ He was apparently a little too vocal about the contents and size of the cargo. In any case, a short time later Darmanovitch was shot dead in the street in Belgrade, where he was meeting his family, and his two killers were also subsequently found only as corpses. So this had been a bit too big for Darmanovitch and his killers.

From then on, Gaddafi’s billions disappeared somewhere in South Africa and few know where they are. In 2012, the first rumors surfaced that considerable assets of the dead dictator were in South Africa. As a result, the transitional Libyan government contacted Eric Goaied, a Tunisian who was a close friend of Gaddafi. He was to search South Africa for the missing assets. Among other things, because the new government needed to build an army and procure over 200 combat helicopters and G5s and other war material for a good five billion, but had no money. When the Libyan government, namely Taha Buishi, confirmed the high finder’s fee (of 10 percent, i.e. $1.25 billion) for the repatriation of the Gaddafi assets, this attracted a few treasure seekers who did not want to miss out on this deal.

Goaied, a Tunisian, contacted his friend Johan Erasmus in South Africa, a former agent of the apartheid regime and a flamboyant arms dealer with good contacts to arms companies like „Denel“ in South Africa but also in Libya. Darmanowitch was also involved in the weapons of war deal. And it was he, after all, who revealed to the Libyans that some of their national wealth was here. He also sent Fannie Fondse, then the head of a special unit of the „ANC Secret Service“ and a special mercenary force that operated in Libya in violation of international law to protect Gaddaffi. During the uprising, the mercenaries had to flee headlong. He also knew Darmanovitch and received the photos with the containers from him.

When Taha Buishi, the Libyan envoy contacted the former head of security of the „ANC“ Tito Maleka and accused the ANC of having appropriated the Gadaffi assets, the latter went with his friend Dr. Jackie Mphaphudi, who knew Winni Mandela well and treated Mandela’s daughter Zondwana Gadaffi Mandela to Jacob Zuma to ask about the missing billions. The latter replied that although he was the President of South Africa, „this is the business of the Minister of Finance, Matthew Phosa.“ Then there was another meeting of high-ranking „ANC“ members on the subject of Libya funds, which Jackie Mphaphudi recorded. Finally, Jackie also organized a meeting between Taha Buishi, the Libyan government representative, and South African President Jacob Zuma at the latter’s estate in Khandla regarding the $12.5 billion that Gadaffi shipped to South Africa in 2010.

So Zuma, Esposa, and some other ANC leaders knew about the money, but they told the Libyan envoys that there had to be a formal request from the Libyan government as to the value of the money. And this request would have to be legitimized by a stable government and signed by the acting Libyan Prime Minister, the Minister of Finance and the Governor of the National Bank as well as by the head of the repatriation authorities. With the Libyan mandate and the belief that they are serving the South African government, Tito Maleka’s team not only wants to clean the dirt off the ANC and put a stop to the looting of the state, but to return the money to the Libyan people.

Mohammed Dschibril, Prime Minister Transitional Government of Libya 2011, met with Zuma and wanted to make it clear to him to get Gaddafi to step down. That didn’t work. But in the spring Zuma flew to Libya, then Zuma calls Jibril for meetings with Zuma and Phosa, but then everything got out of control: apparently Gaddafi gave Zuma money to stay in power and Zuma could help him Gaddafi escape Libya. Matthey Phosa, as treasurer, led the operation to get Gadaffi and his assets out of the country. Both teams come to the same conclusion that Phosa was the key figure. He wanted part of the commission. Fannie has the receipt for „the commission payment.“

So Phosa made his claim to some of the money. He also made that clear to Tito’s team, who had meanwhile booted out Taha Buishi in Libya. As if this were not exciting enough, the treasure hunt thriller has been enriched by a dubious chapter. For Gaddafi’s finance minister, Bashir Al Sharkawi, alias Bashir Saleh, a man now wanted by Interpol for years, is still on the loose in Johannesburg, while Gaddafi’s son Said, who has gone into hiding, is preparing to run for president in unknown exile. After ex Gaddafi’s Johannesburg banker was injured in an assassination attempt and his laptop stolen, he fled the country. In 2018, Zuma was forced to resign due to „state corruption on a grand scale“ and Libya sank into civil war. Now for the next chapter of corruption and kleptocracy in South Africa.

Gupta Leaks: South Africa as prey to Indian klepocrats“.

Human rights lawyer Brian Currin was leaked information in 2017 that came from a Gupta clan laptop. This led him to the trail of a huge corruption scandal that reached the features of state capture by private entrepreneurs. The country at the Cape of Good Hope was systematically plundered. The Guptas made billions in deals in the energy and transportation sectors, laundered the money in Dubai, the Arab Emirates and Hong Kong, and when it got to them, they absconded to Dubai with all the stolen money. The two investigative journalists Susan Comrie and Thanduxolo Jika (Sunday Times/Mail & Guardian) also researched how the South African state looting came about. The Guptas first attracted attention when they flew in some 200 wedding guests by charter plane to military airfields, escorted by police vehicles and security.

The Guptas diverted the costs of about two million dollars for the wedding from the dairy industry through „Estina“ and plundered the contributions for the black farmers for it. The money was laundered with the help of „KPMG“ in Dubai and then used to pay the cost of the wedding in millions. Also „McKinsey“ and „SAP“ profited considerably from the shadow elites and corrupt ministers in the service of the Guptas. Pravin Gordhan, South Africa’s Minister of Finance (2009 to 2014) says that South Africa had a gigantic blackout just weeks after Zuma’s enthronement and that it was no accident. Barbara Hogan, then minister of state-owned enterprises was fired by Zuma. She also comes down hard on him, saying, „Zuma promised gigantic investments in the country’s infrastructure, but we didn’t have the money. „He just didn’t get that,“ Hogan says, and went on to say, „He’s not about the country, he’s not about the problems of South Africa, he’s only about his chosen few.“

The mischief started with Malusi Gigaba when he came into government and successively filled all the important posts in state-owned enterprises with Gupta confidants. Where is most of the public money spent and how do we get it? That was the business model of the three Indian brothers who came to South Africa with their mouse-poor father in 1993. First came „Transnet.“ „Transnet“ manages all airports, train stations and transport companies. Malusi Gigaba appointed Brian Molefi as CEO and Arnosch Sinn as CFO (2 orders for locomotives worth 5 billion went to two Chinese companies) „Mc Kinsey“ received more than a billion for consulting contracts from Salim Essa, business partner of the Guptas. 450 million commission jumped out for the Guptas on the locomotive deal. Money that flowed through offshore companies to Hong Kong and the Arab Emirates. Then Duduzane Zuma, Zuma’s son, came into the picture. He was closely associated with the Guptas and worked with them to perfect corruption and promote kleptocracy.

Also, Cyril Ramaphosas, once a union leader who became a billionaire through the mining company licenses at the end of apartheid, becomes Zuma’s vice president and shortly thereafter travels to Russia for a nuclear deal and the construction of eight nuclear power plants in South Africa that would cost more than $100 billion. US dollars, after which the „Shiva“ uranium mine was bought by the Guptas and Zuma’s son was given a leading position. This was how they positioned themselves for the nuclear deal, which would increase the windfall. And Russia wanted to make South Africa dependent on the donor country, and the Zuma clan, with the help of the Guptas, intended to engage in even greater plundering of the state.

Moe Shaik, head of South African intelligence (2009 -2011) was hired by Zuma, but when the Americans were concerned that the money for the nuclear power plants was coming from Iran, the then head of intelligence had to talk to his boss, President, Zuma about it and unceremoniously resigned from his job because of the disagreement. Zuma is like Trump, only his own interests count. Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, who simply could not conjure up the money for the nuclear deal with Russia, did not fare much better. He was also dismissed and replaced by friends of the Guptas. Desmond van Rooyen was then chosen as the new finance minister, came to the Ministry of Finance with three advisors, but was in office for only four days, then Zuma was forced to remove the trio and replace them with long-time Finance Minister Pravin Gorham because of the protests and huge price drops on the stock market.

From 2016 onwards, there were more and more revelations about the kleptocracy of the Guptas and a courageous ANC member, the then deputy finance minister Mcebesi Jonas, revealed that he had also been offered a ministerial post by the Guptas. Mcebesi was the first to openly voice and criticize the venality of individuals and the tight web of corruption between Zuma, the Guptas and some ANC profiteers. He refused to become a vassal of the Guptas because it would be a stab in the back to South Africa’s hard-fought democracy. The Guptas Leaks confirm the crooked deals with the state-owned corporations „Escom“, „Transnet“ in coal mining and at the arms company „Denel“. In 2015, Brian Molefi is also made the head of „Eskom“ and Arnosch Sinn also joins. The two plunder the company shamelessly and make the Zuma clan and the Guptas much richer.

Mandela would turn in his grave and foam with rage if he saw how quickly the black elite has enriched itself and exploited the country at the Cape of Good Hope. Therefore, we are now leaving South Africa for a trip to the neighboring country of Botswana, which is one of the richest African countries thanks to its diamond mines and, moreover, because of its wealth, has also been able to protect its wildlife better than the surrounding countries. The Central Kalahari and the Okavango Delta, the world’s largest inland delta are also the habitat of the Bushmen and women.

1986-2006: Roaming the Kalahari with the Khoi-San

Botswana can claim to possess all the facets of a sparkling diamond. The grandiose wealth of species in the Okavango Delta of fauna and flora, the multifaceted wilderness that constantly changes its face. An eye-opener as a fence-sitter in Africa’s Garden of Eden, where a vital network of water veins supplies the largely parched southern Africa from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean with the vital elixir. The Okavango, third largest river below the Tropic of Capricorn, originates in the rain-fed highlands of Angola. Although it would only be a few hundred kilometers to the sea, the river heads for the 800,000 square kilometer Kalahari after 1600 kilometers of wandering – and fans out in the world’s largest inland delta.

In bands, the river branches advance into the barren and thirsty desert and form a unique biotope in the middle of the Kalahari. The world’s largest inland delta is about the size of Schleswig-Holstein. 95 percent of all Botswana’s water reserves come from the Okavango Delta, through which more than 18.5 billion liters of water flow in normal years. Almost 80 percent of this water seeps into the sands of the Kalahari. If you look down on the pristine landscape of the Okavango swamps, which is crisscrossed by a labyrinth of river arms, swamps, islands, steppes and lagoons, the Kalahari shimmers to the horizon, sometimes golden yellow, sometimes deep green with blue spots.

In 1986, after my first stay in South Africa with three Swiss guides from London, I set out on an expedition to the Okavango Delta in the neighboring country of Botswana. From Johannesburg we drove with two Landrovers first to Pretoria, then further north until we reached the border river Limpopo, where the first real challenge came. The crossing of the 40 meter wide river could only be done with two vehicles and winches. This means that the winch of the front vehicle is brought across the river by floating or by boat and is attached to a tree there. The second winch is attached to the back of the first vehicle and then it’s off into the water, which just sloshes over the hood. Pulling the front winch and stabilizing it with the rear one with the Landrover standing on the bank requires good cooperation from both vehicle drivers.

The crossing of the Limpopo with the second vehicle takes place then only with the rope winch of the vehicle driven before by the river and runs somewhat more turbulently but nevertheless most smoothly, since one already put a track. Then it went through the Madikgadikdadi Salt Panels, a barren, salt encrusted, pot level salt pan to Maun and from there over Kasane further to the 3rd Bridge, then to the Savuti Channel in the Moremi Game Reserve and finally we arrived at the Victoria Falls. It sounds easy now, but it was a hell of a trip with many lessons on survival in the African wilderness. Luckily, Johann, an experienced and reliable South African safari guide, was there to introduce us to the dangers of the bush experience. It was scary to sleep in a small tent and have a couple of elephants standing in front of or above you, with branches pelting down as they munched on the canopies above us with their trunks.

At first we did not want to sleep in, on or under the Land Rovers and so we surrounded our tent with the Camping Fortunately, our guide had a good ear and sixth sense turned on and warned us one night with the words. „The lions are here, get here quick and climb up on the roof.“ So we hopped nimbly like gazelles with giant leaps to the vehicles and once there, lithely up. And lo and behold, the loud roar of the lions was heard and a considerable pride was immediately surrounding our vehicles. There it would have become most uncomfortable in the tent, because the predators have finally a giant hunger and must feed their babies. Another night I woke up and had to rinse out all the beer we drank every night. So, with the flashlight out of the tent slit, I scanned the area for reflective eyes that would flash in the flashlight’s glow. Still somewhat dazed by the alcohol and the nightly heat over 40 degrees I saw nothing of the kind and wanted already out, there the hippopotamus, which stood directly no two meters before the tent entrance and grazed, ran a few steps further and now I saw significantly more of the nocturnal environment, remained however due to the animal neighbor precaution noiselessly in the tent, because hippopotamuses are the cause of death number 1 in Botswana.

When we finally arrived at the 3rd Bridge, half thirsty after a week of dust-dry tour at over 40 degrees (at night), there was no stopping us when we finally saw the delicious rinsal. Everyone rushed into the hippo and crocodile pool like high-spirited children, happily splashing around as if there were no dangers. We were quite „lucky“ at that time, because this place is teeming with crocodiles, hippos and other wild animals. Later, at the feudal wildlife lodges, a motorboat circled around the swimmers to make sure that no crocodile or hippo was near the bathing guests and developed feeding desires. Another time, while roaming the bush, I had to put an approaching lion to flight by throwing stones, kicking up dust, hissing angrily, and cursing goddamn. What exactly tipped the scales for its majestic retreat, I never learned. In any case, my pulse remained at record levels for a long time. But a stone fell from my fluttering heart.

Then we came across Willy Zingg, a former Swiss military pilot who got stuck here in Botswana and grew into a legend. Not only his fearless alligator prey but also his daredevil flying acrobatics were known far and wide. He was a swashbuckler like in the picture book. We met him at that time under most dramatic circumstances. We were driving towards one of the rarely encountered safari parties in the deserted Okavango Delta and saw, to our horror, that a mighty elephant had taken the one Landrover by the scruff of the neck and was shaking it vigorously with its trunk. Later we learned from Willy that the elephant had been after the oranges.

Next we saw a man sprinting to the other vehicle, who then took off with it without further ado and drove into the elephant’s rear end from behind. This worked in the best way! The elephant turned left with a loud trumpet howl, but in doing so accidentally trampled over a tent in which a woman was lying and whom he then severely injured on the hip during his escape. Yes, such or similarly hot situations there were some on this trip. But we were all spared, thank God. The madness! Another adventurous situation arose when the Swiss safari pioneer had completed his landing strip at the Tsodillo Hills, the sacred mountains of the Khoi-San, the indigenous people of the Kalahari also known as the Bushmen, and wanted to make a sightseeing flight with the San chief.

Since the landing gear would not fold out on landing, the experienced fighter pilot had to do a daredevil loop and roll the plane over in order to deploy the jammed landing gear again thanks to centrifugal force. He succeeded, and the first Bushman to take off into the sky was a bit „gimpy“ and slightly traumatized afterwards, but still brightly enthusiastic. This must have been for the San about the same as if we would suddenly take off with a moon rocket.

At that time, there were about 16,000 Bushmen living in the central Kalahari, and their number is estimated at about 100,000 in the whole of southern Africa. They are masterful trackers, notorious hunters, gifted archers – and true ecologists. They live according to the Eros principle, which connects everything with everything else: „Everything belongs to Mother Nature and Mother Earth. No one owns anything. Everything is shared,“ is how the young Khoi-San Suruka explains to me the worldview of the San at the foot of the Tsodillo Hills, the four sacred, whispering hills with the ancient petroglyphs, the oldest of which are said to be more than 30,000 years old, which probably brings us to the cradle of human civilization. And then there are So in the northwest of the Kalahari lies the great treasure of the Khoi-San, the „Louvre of the Bushmen culture“, so to speak.

To illustrate their closeness to nature, the smallish, tough people with the short, pitch-black curls and peach-colored skin tones tell us about hunting. They coat the shaft of their arrows with a poison they extract from caterpillars. The dose of the poison is chosen precisely depending on the animal that is being killed. Nothing is wasted – not even a drop of the poison. So it is with all other things as well, the Bushmen and their wives take only what they need just to survive. If they dig a fruit or a vegetable out of the ground, they cut it off at the bottom and leave the rest with the roots in the ground so that new shoots can grow again.

The San have learned to survive even in the most inhospitable and arid regions of the Kalahari. This adaptability was born out of necessity, as Suruka continues to tell us, „When the Boers and other white masters threatened us, drove us out and killed us, we had to flee to areas without water. So we filled ostrich eggs with water and buried them in the desert sand. So we could survive there as well. In addition, we Bushmen know no private property, neither fences nor borders. Our rhythm of life is coordinated with the migration of the animals and the tides, and we live according to the principle that nature belongs to all people and that everyone should take only what he needs. Yet for centuries our people have been hunted, driven out and killed like fair game. Perpetrators were other African tribes as well as the European colonial masters among them the Germans.

Today, a road leads from Shakawe to Tsodillo, which Sir Laurence van der Post described in his bestseller „The Lost World of the Kalahari“. Around the steeply rising pyramid hill „Male“ over 6000 years old rock paintings of the Bushmen can be seen. Since June 2002 this cultural site is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The side hills are called „Female“, „Child“ and „Grandschild“ by the San. I had a truly mystical experience while climbing up to the ancient petroglyphs in the jagged rocks. Suruka tried to tell me something in his clicking language, something like that we will come across guards, but I should not be afraid of them. The guards were probably the two rattlesnakes that slithered across before our eyes from one ledge to the other, and from two sides at the same time. If I had been alone, I probably would not have gone on. With Suruka I felt safe and was allowed to marvel at the magical, ancient rock paintings with him. 12 years later I saw a film on the British TV station „BBC“ in which Suruka appeared again and led the film crew to the Tsodillo Hills, just like me at that time.

The Okavango Delta is a uniquely dazzling and almost unearthly natural paradise and an animal kingdom, as long as man remains outside. The government in Botswana, one of the richest African countries, has succeeded well in this thanks to its abundant diamond deposits. It recognized and promoted the benefits of sustainable safari tourism early on and has placed many large areas under protection. I have traveled to the Okavango Delta several times during the 1990s, but then in a more luxurious way with visits to the most expensive luxury lodges of „Wilderness Safari“.

On the game drive with the M’koros, the dugout canoe in which the Tswanas can also transport two adult cattle, we poke through the dense reeds past the hippos, water buffalo and crocodiles to Jao Camp. It’s like gliding on a lily pad over the mirror-smooth surface of the water through the dense reeds, as the edge of the M’koros‘ boat rises only a few inches out of the water. A queasy feeling. If a hippo opens its huge mouth, you could drive the M’koros like into a tunnel. But we were spared this fate thanks to the caution of the attentive and knowledgeable staker. When the author was in the Okavango Delta for the first time before 1986, it was completely dry and had only a few water holes.

With the traditional means of transportation, the M’koros, one did not get very far. On the second visit it was just the other way around. For 46 years, the delta in the African depression had not been flooded so much. Getting around with 4×4 vehicles was impossible in many parts of the Okavango Delta around Moremi and Chief Island. What had happened? Jao Game Ranger Cedric Samotanzi knows the answer: „After tectonic shifts, for the first time the water also came back through the underground network into the Lynanti and Savuti Channel“, so Cederic explained and the phenomenon desert under water.

When the author was in the Okavango Delta for the first time before 1986, it was completely dry and had only a few water holes. With the traditional means of transportation the M’koros (dugout canoes) one did not get very far. On the second visit it was just the other way around. For 46 years, the delta in the African depression had not been flooded so much. Getting around with 4×4 vehicles was impossible in many parts of the Okavango Delta near Moremi and around Chief Island. What had happened? Jao Game Ranger Cedric Samotanzi knows the answer: „After tectonic shifts, for the first time the water also came back through the underground network into the Lynanti and Savuti Channel“, so Cederic explained and the phenomenon desert under water.

Botswana, with its natural environment and unspoiled nature and thanks to the numerous protected reserves, offers the highest concentration of wildlife in southern Africa and therefore spectacular wildlife viewing. Botswana’s greatest treasure is its vast diamond deposits, which make it one of the richest African countries. „Already since 1990, the protection of fauna and flora and the development of ecologically oriented sustainable tourism has enjoyed the highest priority in Botswana, said the then director of the Ministry of Tourism in Botswana Tlhabolongo Ndzinge. Nearly two-fifths of the country is protected natural areas, which are among the largest ecological resources in the world. Botswana is a signatory to the World Trade Organization’s Global Codes of Ethics for Tourism, which set the framework for responsible and sustainable development in the early 21st century. The progressive development of eco- and ethno-tourism is of particular importance for the sustainable development of rural areas.

More than one third of the 90 programs running in Botswana are „community based development projects“. But the problem of illegal poaching is now being exacerbated by a new epidemic affecting elephants as a result of climate change. In 2020 alone, 330 dead animals had been counted in Botswana in the Okavango Delta at the Moremi Game Reserve, and the mysterious mass deaths continued in 2021. At that time, authorities had identified cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, as a possible cause of death. The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) concludes that the mass die-offs have to do with limited access to fresh water and that their habitats are becoming increasingly constricted by livestock farming, among other factors. In addition, the increase in cyanobacteria is due to climate change.

The unspeakable poaching could probably only be stopped if China were to stop imports and drastically control and also consistently enforce import restrictions. So why shouldn’t the international community and the countries of Africa hold the main perpetrator of the slaughter responsible and put massive pressure on China to get the Chinese government to take rigorous action against the elephant leg trade in their own country. China alone, with all its surveillance and education efforts, would be able to make a significant contribution to solving the problem.

Africa’s pioneering wildlife and ecology projects

During more than ten trips to Southern Africa between 1986 and the millennium, I discovered the „Shamwari Game Reserve“ near Port Elisabeth at the Addo Elephant Park in 1993. At that time it was developing into one of the pioneering and in the southern hemisphere unique animal protection and wildlife reintroduction projects. For this purpose, former farmland was renaturalized and converted into bush, after which the „Big Five“ were gradually resettled there. In the early 1990s, Adrian Gardiner, the owner, bought the first five black rhinos from the Natal Parks Board for half a million euros and reintroduced them to the Garden Route near Addo Elephant Park and Port Elisabeth.

During my first visit, the farmland had just been renaturalized and I remember the self-built fire pots and fireplace chimneys with which every single tree stump was smoked out. After a short time, the then 1200 ha farm has become a wildlife sanctuary of over 20’000 ha with a wildlife population of over 10’000 wild animals. This happened in the period from 1993 to 1997. Besides the Long Lee Manor House, the Shamwari Game Reserve has created five other exclusive lodges, which included Eagles Crag and Bushmen River Lodge as well as Lobengula Spa Lodge. In November 2005 Adrian Gardiner received for the sixth time the international award at the „Word Travel Market“ in London (WTM) as „world’s best private game reserve with the highest ecological standards“. In addition, the „Shamwari Game Reserve“ was also classified as the „second most important project in the southern hemisphere“ and received the „British Airways for tomorrow Award“.

Not only this, but also other pioneering eco- and wildlife projects in South Africa and Botswana I accompanied or represented for almost a decade and reported again and again about the progress and obstacles, because I was in South Africa every year and always visited the South African tourism trade fair „INDABA“ in Durban. At the „Londolozi Game“ Reserve of the Varty Brothers, who shot spectacular animal films, I was there from the very beginning and had the right nose, as I did at various places all over the world. Also in Australia with the „Daintree Forest Lodge“ and in Botswana with the „Wilderness Leadership School“ I proved to have a fine sense and was among the absolute top performers of the time. Then there were the „Mara Mara“, „Sabi Sabi“ and „Phinda Game Reserve“ and finally „The Pezula“ in Knysna, where the Swiss tennis ace Roger Federer has his villa. In the noble „Mount Nelson Hotel“ in Cape Town, Margret Thatcher suddenly sat next to me in the hairdressing salon, which made it very easy to talk to the former British Prime Minister. Only the old lady of British politics made a demented impression.

Due to my many contacts in South Africa, I received from the South African Tourist Office (SATOUR) via the embassy contact the assignment to represent South Africa in Switzerland with PR campaigns, whereby I, as a result of my aviation knowledge, also came close to the „South African Airways“ mandate and, as a result of my many visits to South Africa, wrote two travel guides about South Africa. Whether it was about „Ecotourism – and its social significance“ (Bund), the stirring report and successful fundraising campaign for the endangered „Orang Utan in the rainforest of Borneo“ („Brückenbauer“), the „Saving of the whales“ (in the „SonntagsZeitung“) or the „Climate disaster in the Alps“ („Südostschweiz“), I always had my distinctive nose in the (counter)wind and was often far ahead of my time.

This was also the case with the „Swissair scandal“, whose demise I anticipated as early as 1997 in „Der Bund“ with the report „Will Swissair survive?“ and in two other newspapers. Climate change, which today almost 30 years later is still a hot topic and the biggest problem on planet earth, concerned me very early on and I drew conclusions from this and from 1999 onwards largely renounced air travel and for the last 10 years completely. For destinations in Europe I never used an airplane, there the train was announced. Of course, one can rightly accuse me, as a travel journalist, of boosting global air travel with my travel reports, which I cannot deny. But I have always taken the trouble to promote ecologically sustainable projects and environmentally sound travel. and I have always taken a lot of time in one place, usually spending 20-30 days in one country. Finally, I have accepted the radical consequences of not flying, even though it has made my work more tedious and difficult.

Due to my many contacts in South Africa, I received from the South African Tourist Office (SATOUR) via the embassy contact the assignment to represent South Africa in Switzerland with PR campaigns, whereby I, as a result of my aviation knowledge, also came close to the „South African Airways“ mandate and, as a result of my many visits to South Africa, wrote two travel guides about South Africa. Whether it was about „Ecotourism – and its social significance“ (Bund), the stirring report and successful fundraising campaign for the endangered „Orang Utan in the rainforest of Borneo“ („Brückenbauer“), the „Saving of the whales“ (in the „SonntagsZeitung“) or the „Climate disaster in the Alps“ („Südostschweiz“), I always had my distinctive nose in the (counter)wind and was often far ahead of my time.

This was also the case with the „Swissair scandal“, whose demise I anticipated as early as 1997 in „Der Bund“ with the report „Will Swissair survive?“ and in two other newspapers. Climate change, which today almost 30 years later is still a hot topic and the biggest problem on planet earth, concerned me very early on and I drew conclusions from this and from 1999 onwards largely renounced air travel and for the last 10 years completely. For destinations in Europe I never used an airplane, there the train was announced. Of course, one can rightly accuse me, as a travel journalist, of boosting global air travel with my travel reports, which I cannot deny. But I have always taken the trouble to promote ecologically sustainable projects and environmentally sound travel. and I have always taken a lot of time in one place, usually spending 20-30 days in one country. Finally, I have accepted the radical consequences of not flying, even though it has made my work more tedious and difficult.

The press and photo agency business was going like clockwork. Cooperations with leading picture agencies like „Action Press“ and „dpa“ in Germany and „Ringer“, „Keystone“ in Switzerland and the more and more numerous publications as well as the picture archive, which had grown to a good 30,000 slides from almost 50 countries, were a solid basis for my job. In addition, I had set up the cooperation with „Singapore Airlines“ and with „Malaysia Airlines“. An exciting PR mandate, in which I conceived the PR campaigns for „Malaysia Airlines“, planned the ad placements and made many exciting trips and then published the reports. The cooperation with „Singapore Airlines“ lasted almost 15 years. So I came several times to Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, the Maldives and several times to Australia, where I visited almost all states except the Northern Territories and covered thousands of kilometers alone in an off-roader. But back to Africa, one of the most fascinating continents.

Kenya: ICRC mission in the Rift Valley after the ethnic unrest

When I came to Kenya in 2008, I first visited the region near Samburu National Park and was stationed at „Joys Camp“. The Samburu National Reserve is a 165 square kilometer conservation area in central Kenya. The Shaba National Reserve to the east of it belongs to the same ecological area. Characteristic of the area are the very dry habitats for oryx antelopes, gerenuks, grant gazelles, two dikdik and grevyzebras. Also typical of the region are the reticulated giraffes, which are distinguished from other giraffe subspecies by their particularly contrasting coloration. Other ungulate species of the reserve are eland and waterbuck.

Among the predators, lions, leopards, cheetahs and striped hyenas are present here. In addition, the park was once characterized by large herds of elephants and numerous other game species such as waterbuck and Nile crocodiles. However, elephant populations are declining. Their number in the Samburu, Buffalo Springs and Shaba National Reserves was still over 2500 animals in 1973, but by 1976/1977 it had already declined to 531. Now there are even fewer. It was a nice, relaxing trip and then we went on to Mombasa to see the tourist enclave on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

Not far from Mombasa is Haller Park, a wildlife reserve renaturalized by a Swiss. It was extremely impressive! From chimpanzees, macaques, to crocodiles and giant tortoises, there was a great variety of animals. School children came in droves. For them, it was not only their trip to the zoo but also a lesson on wildlife conservation and the importance of their ecosystems, meaning their environment and the behavior of local people that can help preserve wildlife. Exemplary! René Haller grew up in Lenzburg in the canton of Aargau. He learned the profession of a gardener, specialized in landscape design, attended the agronomy course of the „Swiss Tropical Institute“ of the University of Basel before he went to East Africa in 1956. His best known project is the ecological restoration of the mining area of the „Bamburi Cement“. He renaturalized a part of the then devastated large fossil coral lime mining area. Haller is the author of many well-known technical articles and speaker on the topics of ecology/economy and revitalization of devastated industrial agro-lands as well as founder of the „Haller Foundation“, worked as chairman of the „Baobab Trust“ and was a long-time advisory member of the „Kenya Wildlife Service“.

The journey continued to the „Ol Pejeta Rhino & Chimpanzee Sanctuary“ near Mount Kenya. As the name suggests, rhinos are protected from poachers and a large chimpanzee colony is cared for. For the first time I touched the carapace skin of a rhinoceros there, as I stood reverently next to the Landrover and one of these colossi, hoping that the two-ton muscular package regarded me as a harmless sparrow and did not swat me like a fly. Fortunately, nothing actually happened. The rhino would not be disturbed while grazing. After my wildlife adventure lust was quenched, it was back to the humanitarian mission. Back in Nairobi, I went to the „ICRC“ African headquarters and did an interview with Deputy Secretary General James Kisia about the situation of refugees in the Rift Valley after the bloody riots and ethnic displacement, since Kofi Annan was absent. Political unrest in Kenya began on December 30, 2007, the day the official results for the presidential election were released.

Opposition leader Odinga was still in a narrow lead in election forecasts and preliminary results. After incumbent President Mwai Kibaki was declared the winner of the election, protests arose from the opposition party ODM. Its presidential candidate Raila Odinga declared that the election results were fraudulent. In the ensuing unrest, it is estimated that over 1,500 people were killed and 623,692 people, mostly members of the Kikuyu, were forced to flee the violence. Finally, I flew to Eldoret and went to the local „ICRC Red Cross Committee“. With the staff there, I spent three days driving around the refugee camps and looking at the reconstruction projects. It seemed to me that there was still a long way to go back to normality and the misery in the refugee camps with a total of over 100,000 people was very depressing. I had never seen such a scale, not even in South Africa at the time of the ANC-IFP conflict.

Over 10 million Kenyans were starving. Hundreds died daily from water shortages and lack of food. 3.2 million people were affected by acute water shortages at the time. Many of them had to walk up to 30 kilometers a day for a bucket of water and then carry it back. These are some of the staggering figures that the Assistant Secretary General of „ICRC“ and „Red Cross Kenya“ presented to me in his office in Nairobi. And more than 100000 people were staying in refugee camps. At the end of the trip I interviewed Tourism Minister, Najib Balala, whom I also approached about the conflicts and who was surprised about the political flank and questioning about the unrest, but reacted very confidently. From Nairobi, the next mission was back to the Bush. Via Johannesburg, Gabarone and Maun I flew once again to the Okavango Delta to the renowned „Wilderness Wildlife Fund“ Bush lodges and visited the HIV foundation „Children in the Wilderness“.

Namibia: EZA, HIV schools and in the realm of the cheetahs

Due to the many travels and conflict experiences in numerous countries, I finally wanted to get into development cooperation („EZA“) and fly to Namibia via „Interteam“ (a Swiss aid organization) to work locally for three years in the field of tourism and development cooperation, starting in 2011. Specifically, it was a project with the local parastatal organization „NACOBTA“, which wanted to integrate the indigenous people ecologically and more sustainably in the tourism industry to let the indigenous tribes participate in the development. Unfortunately, shortly before the mission, a few foreign aid organizations cut their budget for „NACOBTA“ and so the „EZA“ mission in Namibia was cancelled. Nevertheless, the „Interteam NACOBTA“ assessment made me curious about the Southwest African country with a German colonial past and I decided to travel there.

First, I arranged to meet with the local „Interteam“ representative to see the work on the ground and the challenges of the job. The first thing I was to learn is that helping is not for adventurers, as it was in the 70’s and 80’s when droves of people set out all over the world to show solidarity with local populations or liberation movements. „Know-it-alls and do-gooders“ are out of place in this work. Today’s volunteer work has become very professionalized, said Martin Schreiber, the then managing director of „Unite,“ the umbrella organization of development policy organizations in Switzerland. Today, almost 80 percent of those working in the field have a university degree, and there are also special environmental experts, telecommunications specialists, management coaches, nutritionists and social specialists.

During the one-year assessment, the candidate not only has to reflect on his or her will to persevere and reasons for motivation, but is also confronted with completely different values and religions. At the same time, there would be many hurdles to overcome, such as unreliability of people, the pitfalls of technology and lack of infrastructure, as well as in communication and socio-cultural differences. Finally, each person who is deployed is part of a whole that is constantly adapting to the needs and is in consultative exchange with local partners as to which strategies are being developed. The success of the individual is the success of all.

After this introduction, I met with representatives of „NACOBTA“ in Windhoek and decided to visit a hospital in Rehoboth, which was financed by Swiss people, before I drove across the huge, deserted country and visited the protected wildlife reserves. I also covered a good 5000 kilometers by car in Namibia but relatively little off-road, from the Caprivi Strip in the north, which extends to the four-country corner of Botswana, South Africa, Zimbabwe at Victoria Falls, and down to Fishriver Canyon, the second deepest in the world in the south of the country. First of all, there was Etosha National Park, which was placed under protection as early as 1907, after the formerly rich game population had been reduced to the brink of extinction by poaching and unthinking big game hunting, thus seriously endangering the meat supply of the population.

Today, Etosha National Park impresses with its fantastic animal wealth, which even surpasses the Okavango Delta, as far as giraffes, antelopes and zebras are meant. But not only the wild animals, also the locally resident Herero and Ovambo were mercilessly exterminated after the 1904 uprising, which was fueled by existential fears. Even women and children were not spared by Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha, who acted on behalf of Chief of General Staff Alfred Graf von Schlieffen and also had the support of Kaiser Wilhelm I. This was one of the first genocide.

Unique cheetah conservation project in Ojjowaringo

The „Cheetah Foundation“ (CFF) in Ojjowaringo is one of the impressive wildlife projects with unique experiences. It was the first time I watched these noble, elegant predatory cats in the wild and hunting for some poor rabbits, which were thrown to the cheetahs as breakfast food. CCF’s Namibian cheetah population study has been ongoing since 1990, with over 750 tissue samples and 1000 fecal samples collected to date. These samples allow research on Namibian cheetah populations over a 30-year period. Population monitoring within the 50,000 hectare game reserve is made possible by combining it with genetic analysis via microsatellite markers. This allows CCF researchers and game rangers to identify individual cheetahs based on both visual and genetic characteristics.

A key challenge in rural Namibia is building capacity to manage human-wildlife conflict. „CCF“ has identified several landscapes in central-northern and central-eastern Namibia that require an urgent focus on science-based solutions to mitigate human-wildlife conflict (HWC).Key focus regions include the Greater Waterberg Landscape, the Gobabis Landscape, and large areas of communal land in eastern Namibia’s Kalahari ecosystem. In Namibia, 80 percent of wildlife lives outside of protected areas, but in some areas such as the eastern communal lands, the absence of wildlife threatens species such as wild dogs, cheetahs, and leopards that prey on livestock.

One of the biggest challenges in these rural areas is managing human-carnivore conflict. Cheetahs and other predators, including leopards, African wild dogs, brown hyenas, and jackals, live in large territories on livestock areas.To reverse the situation, a research-based solution that involves the community is needed. To this end, B2Gold, a Canadian gold mining company with a presence in Namibia, has provided $50,000 to support conservation research and outreach programs for communities living with carnivores. With support from B2Gold, „CCF“ has developed a comprehensive research project to assess key strategies and approaches to reduce human-carnivore conflict. The research will inform conservation efforts aimed at improving rangeland, livestock, and wildlife management, reducing livestock loss on open cropland, and restoring habitat.

The „CCF“ hosts a world-class research facility unique in Africa. The „Life Technologies Conservation Genetics Laboratory“ is the only fully equipped on-site genetics laboratory in a conservation facility in Africa. From this facility, „CCF“ collaborates with scientists around the world. The research benefits not only the cheetah and its ecosystem, but also other big cats and predators. Trained dogs to recognize the droppings also help. The poop dogs use various signals to their handler to indicate what type of animal feces is present. Once the sample is collected, it is taken to the lab. DNA is extracted to identify individual cheetahs and understand population structures of cheetahs and other carnivores.

At a later date, in the very south of Namibia, at the Fish River Canyon and the Giants Playground, we drove around with a farmer on his huge farm and there we met two magnificent cheetahs in the wild, which we approached on foot to sniff each other, because they crept slowly and smoothly towards us on their velvet posts and had obviously become accustomed to humans and knew no shyness. Nevertheless, they did not behave like tame house cats. As I soon surprisingly lay on the ground under the snout of the animal and took close-up pictures from there, the very close contact with the dangerous cuddly cats ended in the end against expectation for me with feelings of happiness instead of deadly bites. But the tingling feeling of lying under a wild cat as its prey, so to speak, only holding the camera protectively in front of my face, was already an adrenaline rush of the first order that I will never forget.

After this wonderful experience in the realm of wildlife, I would like to add a dark chapter of colonial history.

Genocide, Slavery, Land Theft, Rape, Humiliation

In 1884, Africa is partitioned among the European powers and colonial masters at the Congo Conference in Berlin. Germany rises to colonial power, whereupon German Southwest Africa, now Namibia, was officially established and developed into a colony. By 1914, some 15,000 white settlers had arrived in German Southwest Africa, including more than 12,000 Germans. The German colonial administration ruled the area with the help of racial segregation and oppression. The natives were treated as second-class people by the European settlers and were practically disenfranchised. Native tribes were forced to clear their land. Vital grazing land thus increasingly passed into the hands of the settlers. This threatened the livelihood of the semi-nomadic Herero pastoralists.

Slavery, land theft, public execution, forced labor, rape and humiliation became the doctrine and agenda for the oppressed population. With Samuel Maharero, the uprising against the white occupiers began in 1904. The Na’ama chief, Capitain Hendrik Witboo was the icon of the anti-colonial resistance. He accused the Ovambo leader of cooperating with the so-called „protecting power“ of the Germans, thus opening the floodgates for conquest. Only after 20 years of oppression by the Herrenmenschen, the peoples of Namibia for the first time unitedly resisted their oppressors.

On January 12, 1904, the first shots were fired against the occupiers. The insurgents besieged military stations, blocked rail lines and raided trading posts. In the first months of the war, the Herero dominated the fighting. The representatives of the German Empire were surprised by the uprising. The governor of German Southwest Africa, Theodor Leutwein, was ordered to put down the rebellion militarily. In May 1904, the command was transferred to Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha. Von Trotha purposefully conducted the clashes as a war of extermination.

The 2,000-strong imperial Schutztruppen were reinforced by 14,000 soldiers, who proceeded with brutal harshness against the insurgents. He wrote: „I want my troops to go out there and wipe the whole community off the face of the earth. Clean it up, hang it up, gun it down! I destroy the insurgent tribes with streams of blood and money. Inside the German border, every Herero will be shot, with or without a rifle, with or without cattle. I will take no more women and children, drive them back to your people or have them shot.“ Then Von Trotha issued the extermination order and the genocide took its course.

In August 1904, the German army had surrounded the Herero people on the Waterberg plateau. The cornered Herero were forced to flee to the Omaheke Desert, which the Germans sealed off with a 250-kilometer cordon. During the Battle of Waterberg, about 85,000 people starved and died of thirst in agony because the Germans had poisoned and surrounded the water holes. In total over 100’000 people were murdered by the German occupiers, the survivors enslaved, tortured and interned, Shark-Island is only one of many concentration camps in the country.

In Swakopmund on the Atlantic coast, right in front of the town hall stands the stone of contention: the war memorial of the German navy, which honors the German soldiers who killed over 100,000 people here. This annoys the city deputy Uahimisa Kaapehi massively. „The monument should be torn down, thrown in the garbage or shipped to Germany“. Even more shocking is that to this day Germany has not officially apologized to the Namibian peoples for the first genocide in history. Nor has any land been returned that was stolen from the natives at the time. Even today, the owners of large farms and the towns are owned by the Germans, while for the Hereros and Na’ama’s only unemployment and hopelessness remained.

The genocide of the Hereros and Namas and the concentration camps and methods of extermination were the model for Nazi fascism and for apartheid in South Africa. Discrimination and oppression against both populations continued until World War I. German colonial rule over Southwest Africa did not end until 1915, when the imperial Schutztruppen surrendered to South African troops of the British Empire. Namibia was the last African country to become independent in 1990 after a nearly 25-year struggle for freedom by SWAPO against the mandate power of South Africa. Vekuii Rukuro, the head of the Herero, says: „This is how three generations have been ruined for over 100 years. Driven from their land, from their grazing grounds, driven into poverty from the graves of their ancestors. And the suffering has no end!

In the south of the country in Maltahöhe, HIV mortality was particularly high, and there were almost 40 percent orphans at that time who lost either one or even both parents in the 1980s and early 1990s. And so there is also an HIV orphan school in Maltahöhe, where poverty and unemployment are particularly high. It was moving to listen to the „Oa Hera“ children’s choir, which is supported by the backpacker camp. The bright, poignant angelic voices of the orphans impressed me as much as the wealth of imagination and creativity in the school with design tools or children’s toys. And when one considers the dangers the school children face on their considerably long marches in this inhospitable region, the composure and cheerfulness of the children in the face of their difficult fate is astonishing.

South Africa: A Gnu herd in the bush at Shamwari Game Reserve near Port Elisabeth in the Western Cape Province

South Africa: a old bushmen woman in the Drakensberge opening an oostrich egg

South Africa: Two lions in love at Shamwari Game Reserve licking and cleaning each other skin

South Africa: A rhino facing a bird while greasing in Shamwari Game Reserve

South Africa: Safari through the high Savanna gras looking for wild life

A rhino at Shamwari Game Reserve near Port Elisabeth, Western Cape Province, South Africa, wilderness, tour

South Africa: Two lions in love at Shamwari Game Reserve licking and cleaning each other skin

South Africa: A rhino facing a bird while greasing in Shamwari Game Reserve

South african women with her baby under the umbrella to protect them from the hot sun

Zürich-City: Nelson Mandela’s speach on his first foreign visit in Switzerland after elected as president and for the nobel prize at the Dolder Hotel in front of the swiss economy-elite

South Africa: Around 6000 prisoners are inside the Pollsmoor jail outside of Cape town

Zürich-City: Nelson Mandela’s speach on his first foreign visit in Switzerland after elected as president and for the nobel prize at the Dolder Hotel in front of the swiss economy-elite

Zürich-City: Nelson Mandela’s speach as president and nobel prize winner at the Dolder Hotel in front of the swiss economy elite

Zürich-City: Nelson Mandela’s speach as president and nobel prize winner at the Dolder Hotel in front of the swiss economy elite

The Shamwari Game reserve near Port Elisabeth was voted more than seven times as the world best safario and eco-tourism-game reserve

Red Cross South Africa Civil War Ntunzini94

Südafrika: Stellenbosch Wineyards, beautyfull scenery, wines & spa’s. Wellness, Gesundheit, Winzer, Weingüter,

Swiss Photojournalist Gerd Müller standing in front of DC3 of SAA Historic Flights Aircraft in Durban, South Africa

Humanitäre Engegement des Fotojournalisten Gerd Müller. Er begleitet einen Rot Kreuz Südafrika Einsatz im Bürgerkrieg. Red Cross South Africa blessed employee and car during the civil war of IFP and ANC.Bildreferenz: ZA_ICRC-ANC-IFPConflict1307

Gerd Müllers Humanitärer Einsatz mit dem «Red Cross South Africa». Rot Kreuz Südafrika Rettungswagen im Einsatz während des Bürgerkrieges zwischen IFP und ANC. Red Cross South Africa blessed employee and car during the civil war of IFP and ANC.Bildreferenz: ZA_ICRC-ANC-IFPConflict2143